Tema 2: Análisis multivariado de series temporales(3)

VARX(p)

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

VARX(p)

- Vamos a enfocarnos en el modelo VAR(p) con posibilidad de incluir covariables (variables exógenas):

\[X_{t}=CD_t+\phi_1 X_{t-1}+...+\phi_pX_{t-p}+a_{t}\] donde \(\phi_0\) es un vector de dimensión \(k\), \(\phi_i\) matrices \(k \times k\) para \(i=1,...,p\), \(\phi_p \neq 0\) y \(a_t\) es una secuencia de i.i.d. vectores aleatorios con media 0 y matriz de covariancias \(\Sigma_a\), que es definida positiva, \(C\) es la matriz de coeficientes de dimiensión \((k \times M)\) y \(D_t\) es el vector columna de variables exógenas \((M \times 1)\).

Su representación con el operador autorregresivo es \[\phi(B) X_{t}=CD_t+a_{t}\] donde \(\phi(B)=I_k- \phi_1 B-...- \phi_p B^p\) es el operador autorregresivo.

Si las soluciones de \(|\phi(B)|\), están fuera del círculo unitario, entonces VARX(p) es estacionario.

VARX(1)

- VARX(1) con 3 series tepmorales y variables exógenas: intercepto y tendencia.

\[X_{t}=C D_t+\phi X_{t-1}+a_{t},\]

\[\text{donde}~~ C=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha_{1} & \beta_{1} \\ \alpha_{2} & \beta_{2} \\ \alpha_{3} & \beta_{3} \end{bmatrix} ~~\text{y}~~ D_t= \begin{bmatrix}1 \\ t \end{bmatrix}\]

- Es decir,

\[X_{1,t}=\alpha_1 + \beta_1 t+\phi_{11}X_{1,t-1}+\phi_{12}X_{2,t-1}+\phi_{13}X_{3,t-1}+a_{1,t}\]

\[X_{2,t}=\alpha_2+ \beta_2 t+\phi_{21}X_{1,t-1}+\phi_{22}X_{2,t-1}+\phi_{23}X_{3,t-1}+a_{2,t}\]

\[X_{3,t}=\alpha_3+ \beta_3 t+\phi_{31}X_{1,t-1}+\phi_{32}X_{2,t-1}+\phi_{33}X_{3,t-1}+a_{3,t}\]

Causalidad de Granger

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

Causalidad de Granger de un VAR(1)

- Considere el modelo VAR(1):

\[X_{t}=\phi_0+\phi_1 X_{t-1} + a_{t}\] - Expresando explícitamente la ecuación,

\[\begin{bmatrix}X_{1,t}\\ X_{2,t} \end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}\phi_{10}\\ \phi_{20} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix}\phi_{1,11} & \phi_{1,12} \\ \phi_{1,21} & \phi_{1,22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}X_{1,t-1}\\ X_{2,t-1} \end{bmatrix} +\begin{bmatrix}a_{1,t}\\ a_{2,t} \end{bmatrix}\]

- O bien,

\[X_{1,t}=\phi_{10}+\phi_{1,11}X_{t-1,1}+\phi_{1,12}X_{t-1,2}+a_{1,t}\]

\[X_{2,t}=\phi_{20}+\phi_{1,21}X_{t-1,1}+\phi_{1,22}X_{t-1,2}+a_{2,t}\]

- Habíamos discutido que \(X_{1,t}\) causa a \(X_{2,t}\) en el sentido de Granger si \(\phi_{1,21} \neq 0\).

Causalidad de Granger de un VARX(p)

- Recordemos que el modelo VARX(p) se puede representar por:

\[X_{t}=CD_t+ \sum_{i=1}^p \phi_i X_{t-i}+a_{t}\]

- Podemos representar este modelo por bloques. Considere dos subvectores de \(X_t\), i.e. \(X_t=(\dot{X}_{1,t},\dot{X}_{2,t})\) donde \(\dot{X}_{1,t}\) de dimensión \(k_1\) y \(\dot{X}_{2,t}\) de dimensión \(k_2\) y \(k=k_1+k_2\).

\[\begin{bmatrix}\dot{X}_{1,t}\\ \dot{X}_{2,t} \end{bmatrix} = CD_t + \sum_{i=1}^p \begin{bmatrix}\Phi_{i,11} & \Phi_{i,12} \\ \Phi_{i,21} & \Phi_{i,22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\dot{X}_{1,t-i}\\ \dot{X}_{2,t-i} \end{bmatrix} +\begin{bmatrix}\dot{a}_{1,t}\\ \dot{a}_{2,t} \end{bmatrix}\]

- Note que ahora los elementos de la matriz de coeficientes \(\Phi_{i,12},\Phi_{i,12},\Phi_{i,21},\Phi_{i,22},~i=1,...,p\) son matrices también.

Causalidad de Granger de VAR(1) con \(k=3\)

\[\begin{bmatrix}X_{1,t}\\ X_{2,t}\\ X_{3,t} \end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha_{1}\\ \alpha_{2}\\ \alpha_{3} \end{bmatrix}+\begin{bmatrix}\phi_{1,11} & \phi_{1,12} & \phi_{1,13} \\ \phi_{1,21} & \phi_{1,22} & \phi_{1,23}\\ \phi_{1,31} & \phi_{1,32} & \phi_{1,33} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}X_{1,t-1}\\ X_{2,t-1}\\ X_{3,t-1} \end{bmatrix}+a_{t}\]

Suponga que nos interesa ver la causalidad de Granger entre \(X_{1,t}\) y \((X_{2,t},X_{3,t})\), i.e. \(X_t=(\dot{X}_{1,t},\dot{X}_{2,t})\) donde \(\dot{X}_{1,t}=X_{1,t}\) y \(\dot{X}_{2,t}=(X_{2,t},X_{3,t})\) con \(k_1=1\) y \(k_2=2\).

En este caso,

\[\Phi_{1,11}=\left[\phi_{1,11}\right],~~\Phi_{1,12}=\left[\phi_{1,12},\phi_{1,13}\right]\] \[\Phi_{1,21}=\begin{bmatrix}\phi_{1,21}\\ \phi_{1,31} \end{bmatrix},~~~\Phi_{1,22}=\begin{bmatrix} \phi_{1,22} & \phi_{1,23}\\ \phi_{1,32} & \phi_{1,33}\end{bmatrix}\]

\[\begin{bmatrix}\dot{X}_{1t}\\ \dot{X}_{2t} \end{bmatrix} = CD_t + \sum_{i=1}^p \begin{bmatrix}\Phi_{i,11} & \Phi_{i,12} \\ \Phi_{i,21} & \Phi_{i,22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}\dot{X}_{1,t-i}\\ \dot{X}_{2,t-i} \end{bmatrix} +\begin{bmatrix}a_{1t}\\ a_{2t} \end{bmatrix}\]

- Para contrastar la hipótesis de que el subvector \(\dot{X}_{1t}\) no cause a \(\dot{X}_{2t}\) en el sentido de Granger sería contrastar:

\(H_0:\Phi_{i,21}=0\) para todo \(i=1,...,p\)

\(H_1:\Phi_{i,21} \neq 0\) para algún \(i=1,...,p\).

- Considere \(\beta\) el conjunto de todos los parámetros de interés, i.e. todos los elementos de \(\left[\phi_1,...,\phi_p,C\right]\), podemos escribir las restricciones en la siguiente ecuación \[\Gamma \beta=c\] en donde \(\Gamma\) es una matriz \((N \times (k^2p+kM))\).

Para probar la causalidad de Granger, se utiliza el estadístico de Wald para probar la hipótesis. Este estadístico tiene una distribución asintótica de \(F(pk_1k_2,kT-n^*)\) donde \(n^*\) es la cantidad total de parámetros del modelo.

Por otro lado, para probar la causalidad instantánea, se utiliza el estadístico Wald pero con las hipótesis planteadas de la siguiente forma:

\[\begin{align}H_0:&\Gamma \Sigma_a=c \\ H_1:&\Gamma \Sigma_a \neq c \end{align}\]

donde \(\Gamma\) es una matriz \((N \times K(K+1)/2)\)

- En este caso, el estadístico tiene una distribución asintótica de \(\chi_{N}^2\).

Ejemplo simulado

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

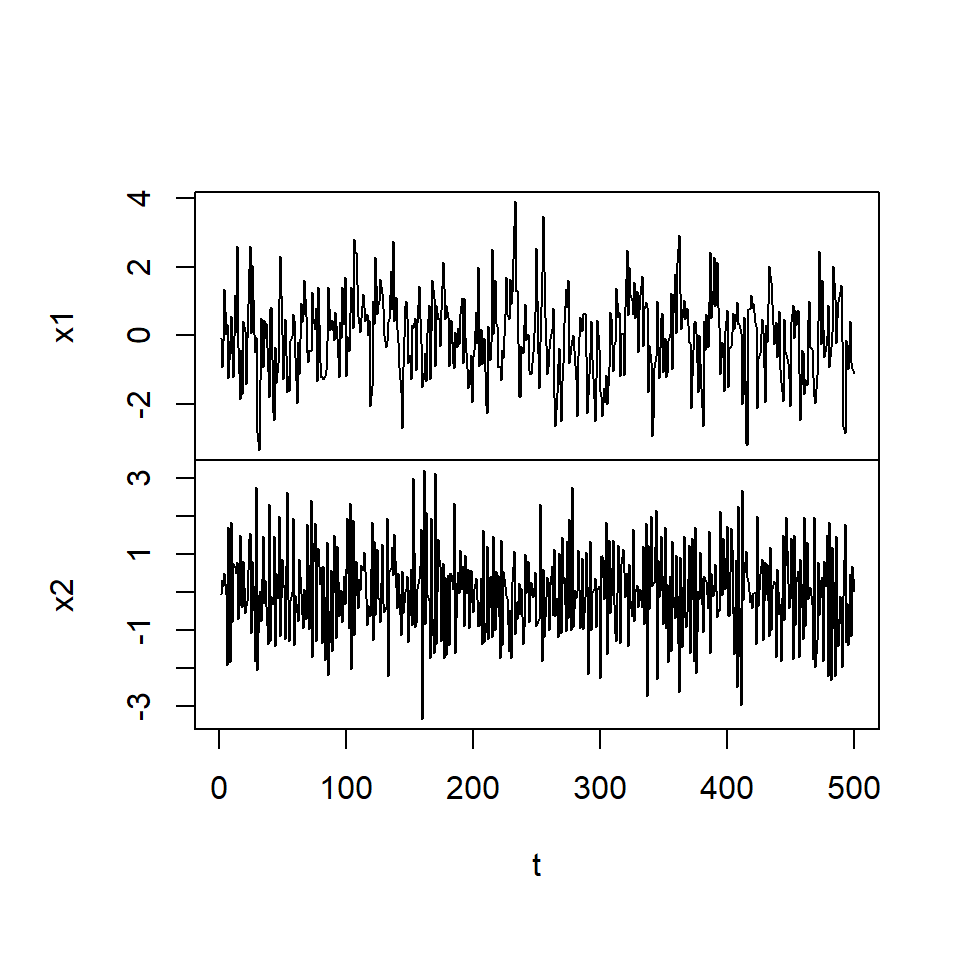

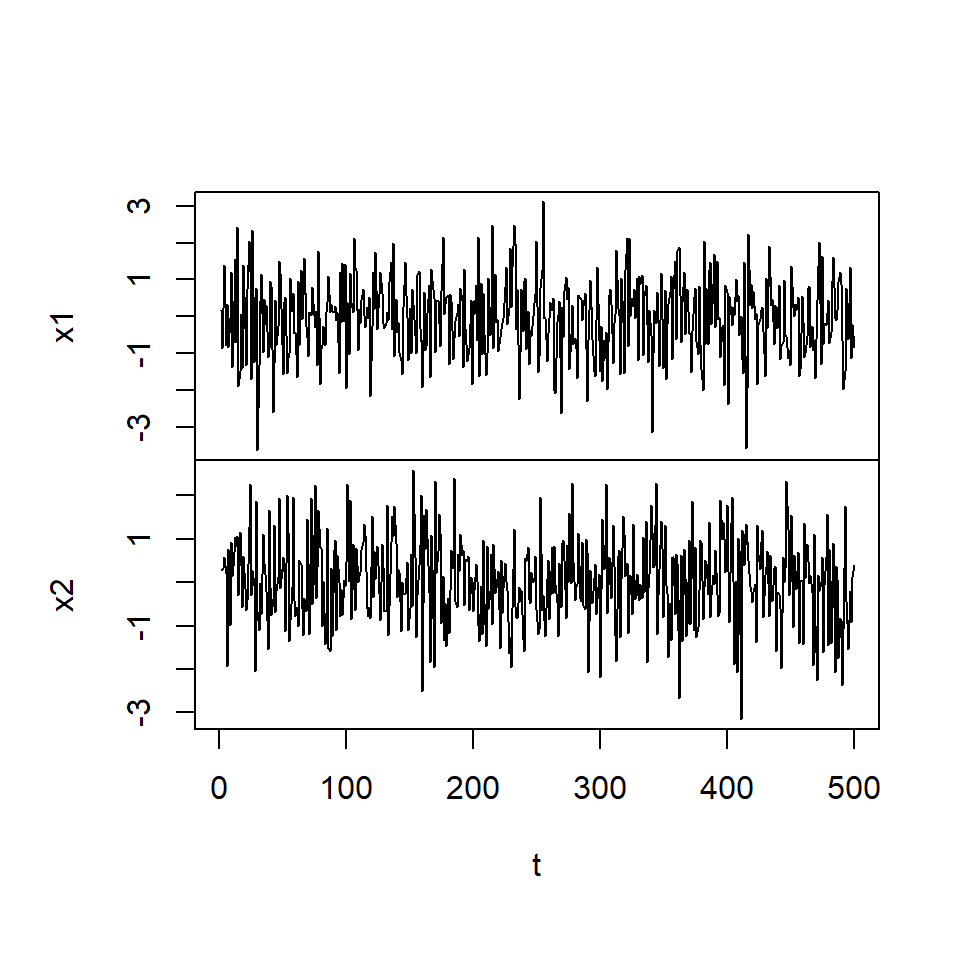

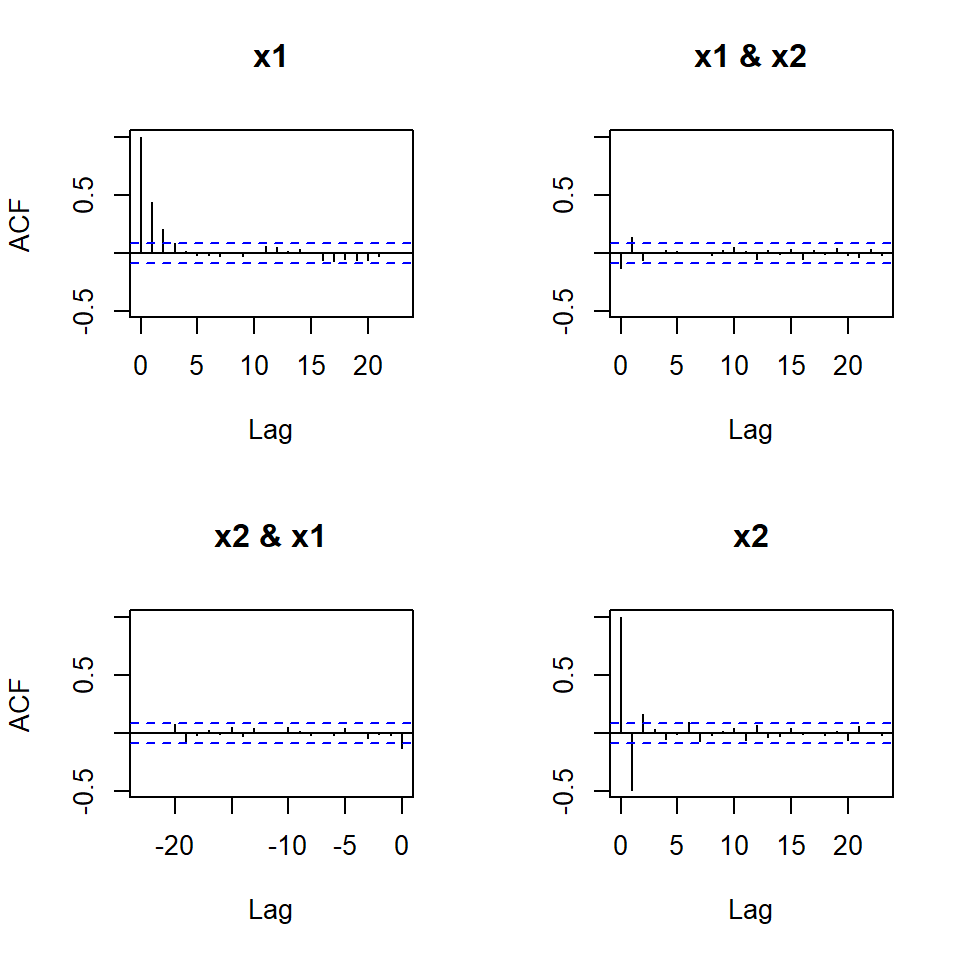

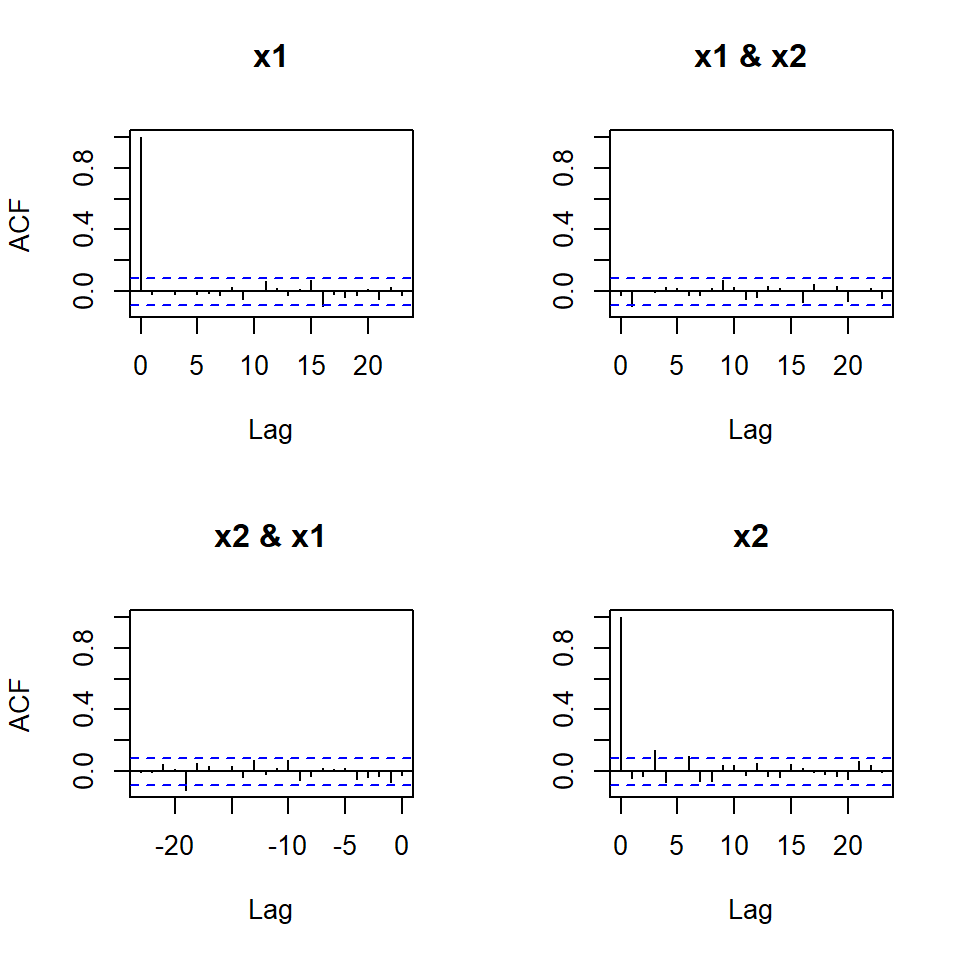

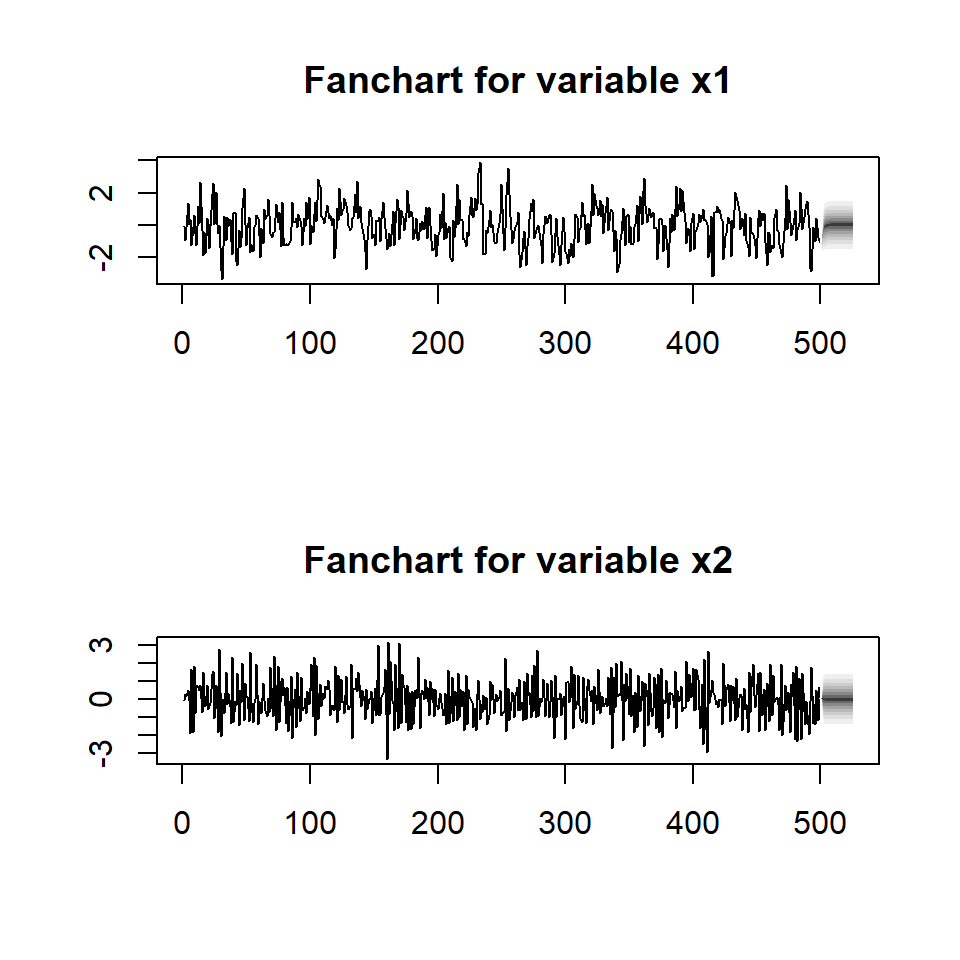

Ejemplo simulado

- Considere una realización de \(T=1000\) de un VAR(1):

\[\begin{bmatrix}X_{1t}\\ X_{2t} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.5 & 0.3 \\ 0 & -0.5 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}X_{1,t-1}\\ X_{2,t-1} \end{bmatrix} +\begin{bmatrix}a_{1t}\\ a_{2t} \end{bmatrix}\] donde \(a_t \sim N(0,\Sigma_a)\) con \(\Sigma_a=I_2\).

Estimación de modelos

vars::VARselectselecciona el mejor modelo de acuerdo con los diferentes criterios de información.

$selection

AIC(n) HQ(n) SC(n) FPE(n)

1 1 1 1

$criteria

1 2 3 4 5

AIC(n) 0.06069770 0.06529851 0.06971828 0.08414479 0.09290304

HQ(n) 0.07403563 0.09197436 0.10973206 0.13749649 0.15959267

SC(n) 0.09467393 0.13325096 0.17164695 0.22004968 0.26278416

FPE(n) 1.06257774 1.06747838 1.07220862 1.08779250 1.09736740vars::rootsverifica que los módulos de los autovalores son menores a 1.

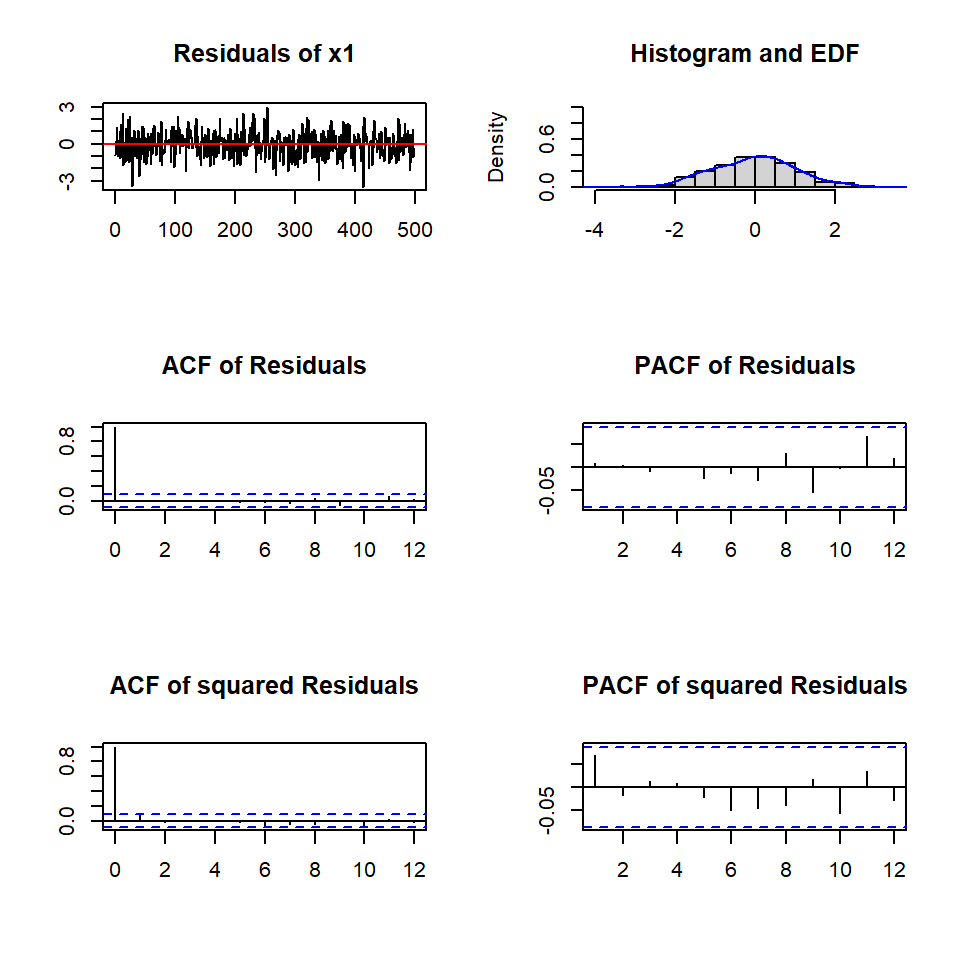

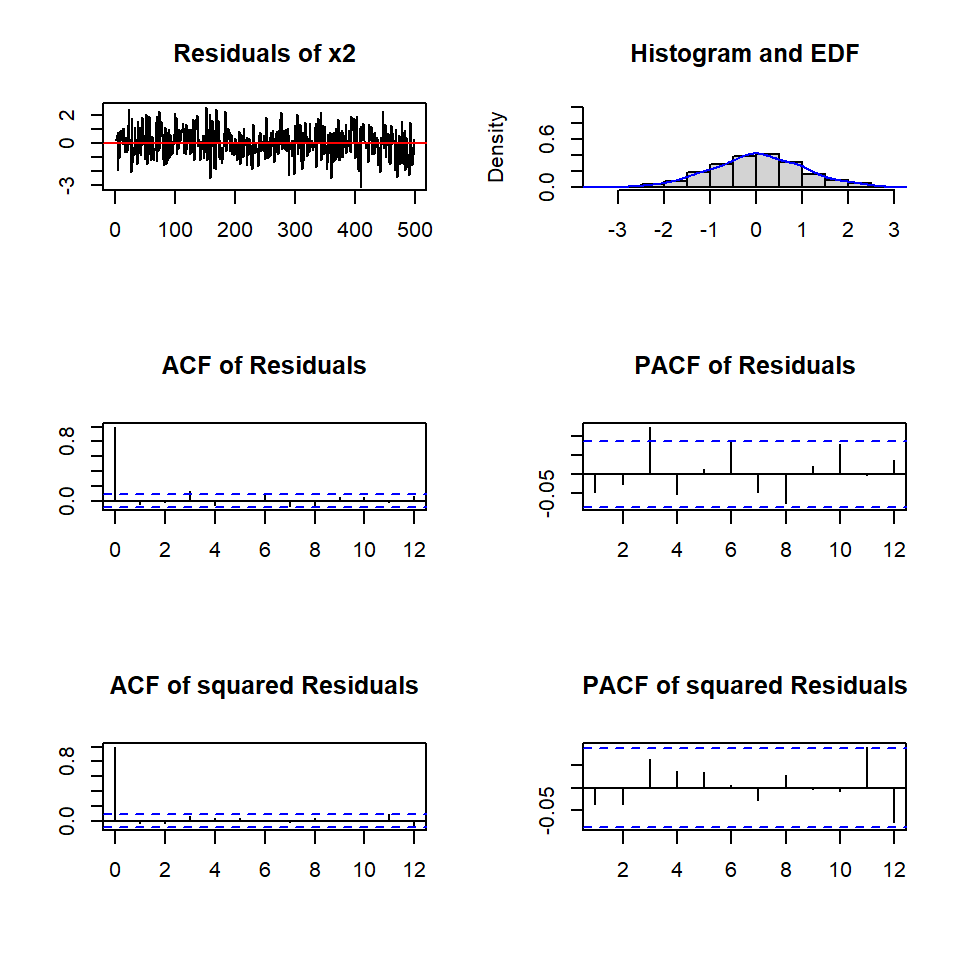

Los diagnósticos

Portmanteau Test (asymptotic)

data: Residuals of VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 61.324, df = 60, p-value = 0.4283

ARCH (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 47.647, df = 45, p-value = 0.3655$JB

JB-Test (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 1.0368, df = 4, p-value = 0.9042

$Skewness

Skewness only (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 0.8841, df = 2, p-value = 0.6427

$Kurtosis

Kurtosis only (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 0.15267, df = 2, p-value = 0.9265$Granger

Granger causality H0: x2 do not Granger-cause x1

data: VAR object varsimest

F-Test = 26.547, df1 = 1, df2 = 994, p-value = 3.102e-07

$Instant

H0: No instantaneous causality between: x2 and x1

data: VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 0.52202, df = 1, p-value = 0.47$Granger

Granger causality H0: x1 do not Granger-cause x2

data: VAR object varsimest

F-Test = 5.3275, df1 = 1, df2 = 994, p-value = 0.0212

$Instant

H0: No instantaneous causality between: x1 and x2

data: VAR object varsimest

Chi-squared = 0.52202, df = 1, p-value = 0.47Pronóstico

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

Pronóstico

- Dadas las observaciones \(X_1,...,X_T\), el pronóstico \(h\) pasos para frente, \(X_{T+h}\) es dado por

\[X_{T}(h)=CD_{T+h}+\phi_1 X_{T+h-1}+...+\phi_pX_{T+h-p},\] donde \(X_{T}(j)=X_{T+j}\) para \(j\leq 0\).

El error de pronóstico de \(h\) pasos para frente es dado por \[e_h(h)=X_{T+h}-X_{T}(h)\]

El cálculo del error de pronóstico de \(X_{T}(h)\) es más conveniente usar la representación de MA, y el error de pronóstico es dado por

\[X_{T}(h)= a_{T+h} + \phi_1 a_{T+h-1}+...+\phi_{h-1} a_{T+1},\]

Ejemplo

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

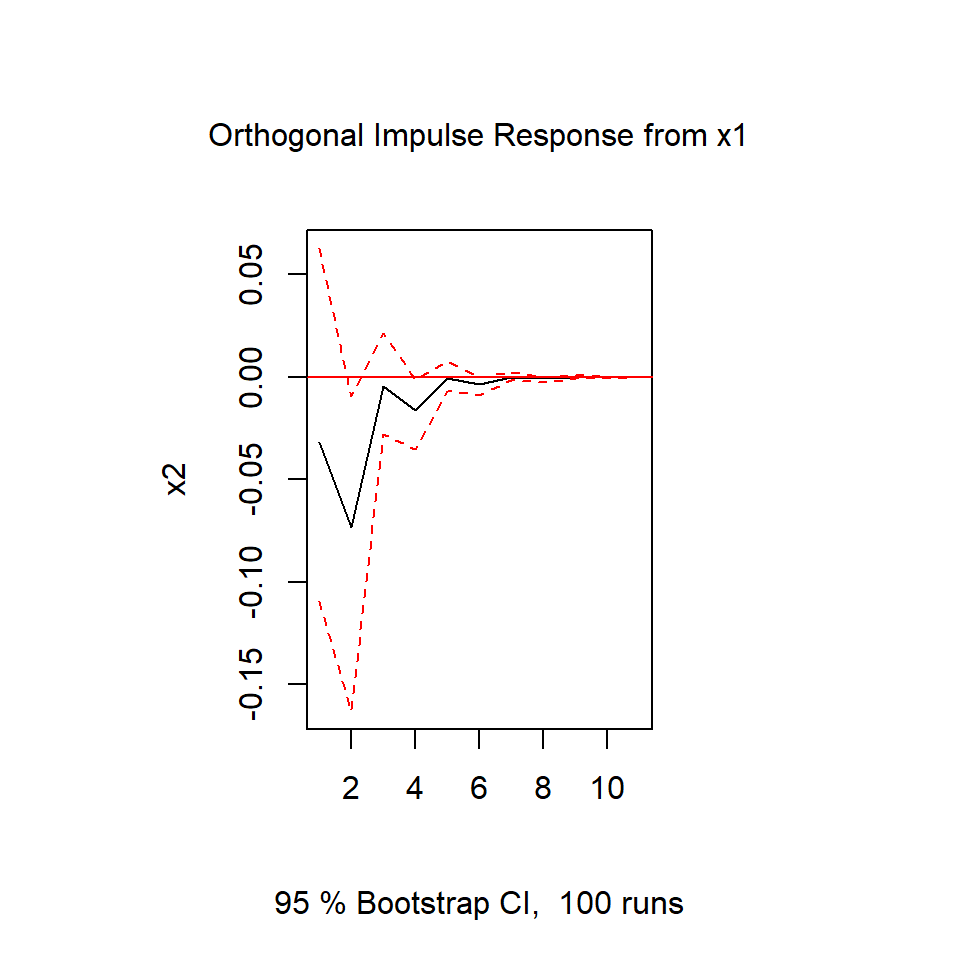

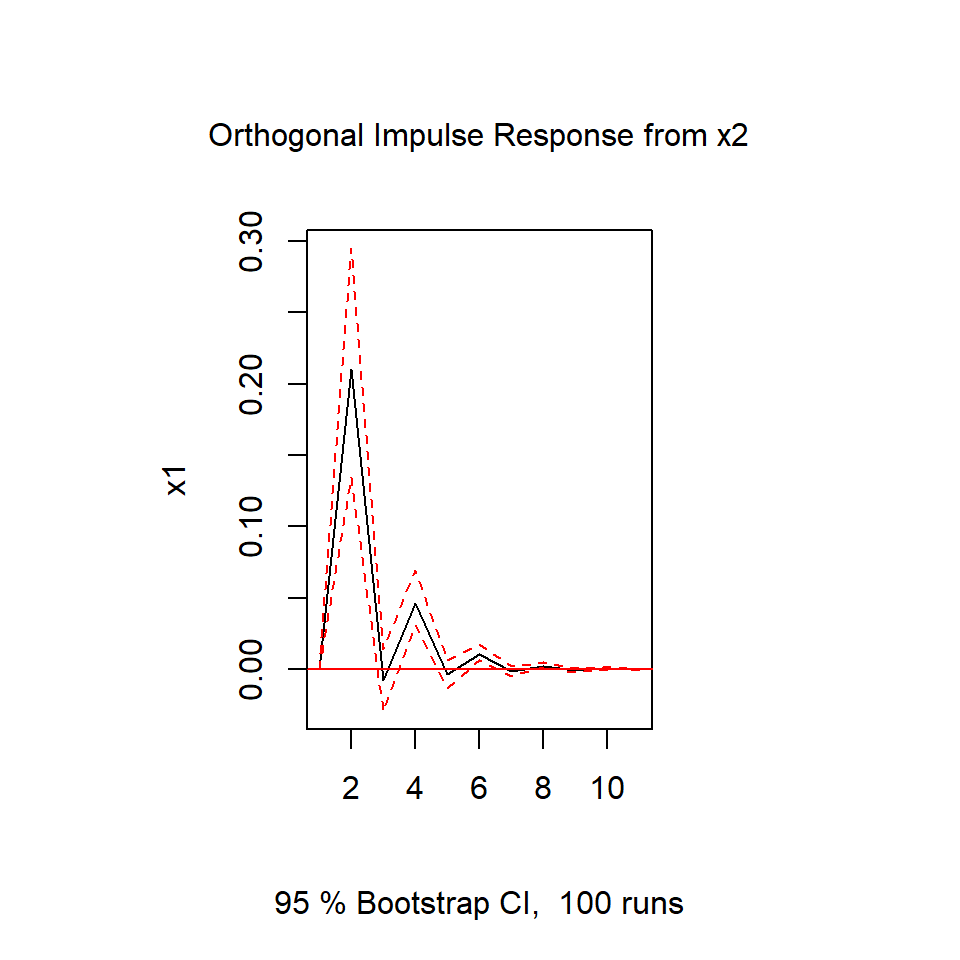

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

- Para cualquier modelo VAR(p) estacionario, tiene la representación de MA:

\[X_{t}= \theta_0 a_{t}+\theta_1 a_{t-1}+ \theta_{2} a_{t-2}+...\]

Se interpreta como una regresión en donde cada entrada \((i,j)\) de \(\theta_m,~m=1,...\) representa el cambio del valor esperado de \(X_{j}\) bajo un cambio de una unidad de \(X_i\).

Por ejemplo, para el modelo:

\[\begin{bmatrix}X_{1t}\\ X_{2t} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\theta_{0,11} & \theta_{0,12} \\ \theta_{0,21} & \theta_{0,22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}a_{1,t}\\ a_{2,t} \end{bmatrix} +\begin{bmatrix}\theta_{1,11} & \theta_{1,12} \\ \theta_{1,21} & \theta_{1,22} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}a_{1,t-1}\\ a_{2,t-1} \end{bmatrix}+\dots\]

\(\theta_{1,21}\) representa el cambio del valor esperado de \(X_{2,t+1}\) bajo un cambio de una unidad de \(X_{1,t}\).

\(\theta_{1,12}\) representa el cambio del valor esperado de \(X_{1,t+1}\) bajo un cambio de una unidad de \(X_{2,t}\).

Ejemplo simulado

Ejemplo

Contenido

VARX(p)

Causalidad de Granger

Ejemplo simulado

Pronóstico

El análisis del impulso-respuesta

Ejemplo

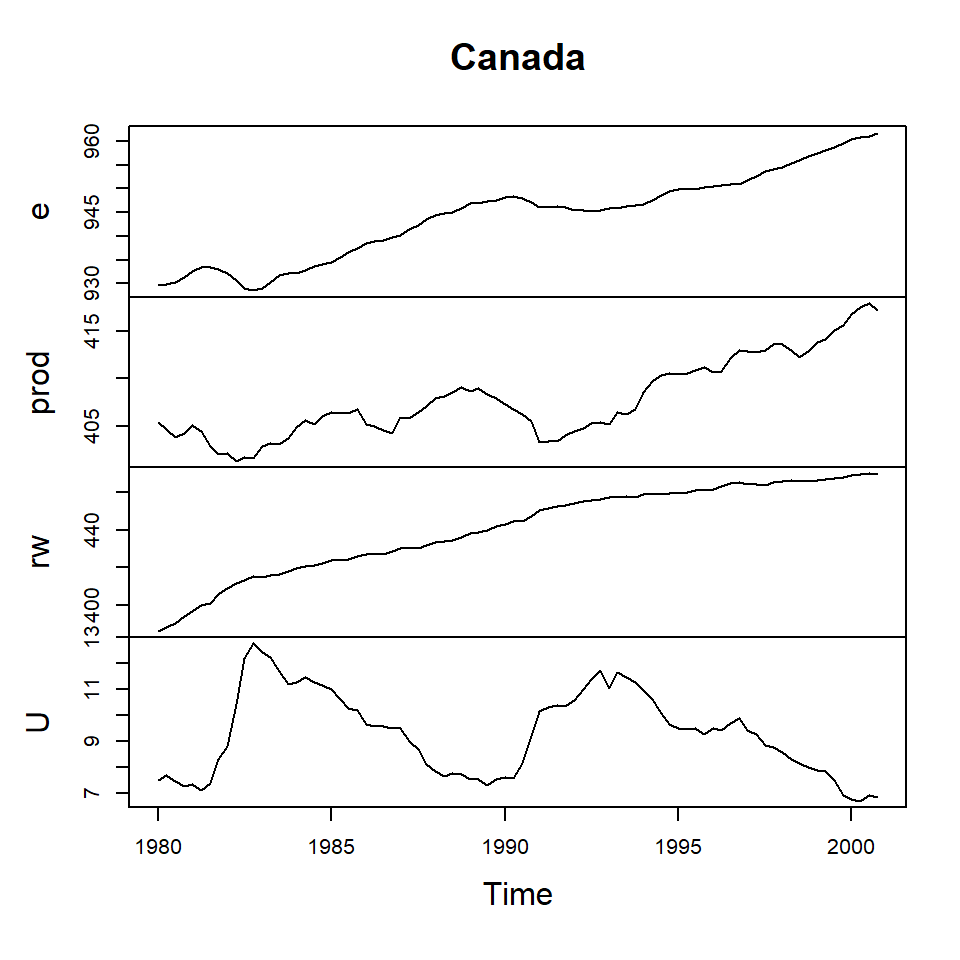

Ejemplo: series macroeconómicas en Canada

Estimación

$selection

AIC(n) HQ(n) SC(n) FPE(n)

3 2 1 3

$criteria

1 2 3 4 5

AIC(n) -6.457999837 -6.862930587 -6.9695915550 -6.826230019 -6.696865092

HQ(n) -6.159906898 -6.366109023 -6.2740413655 -5.931951204 -5.603857651

SC(n) -5.710735482 -5.617489996 -5.2259747277 -4.584436956 -3.956895792

FPE(n) 0.001570168 0.001052827 0.0009575467 0.001128994 0.001329669

6 7 8 9 10

AIC(n) -6.687175990 -6.55982329 -6.584746129 -6.493397603 -6.523612352

HQ(n) -5.395439924 -5.06935860 -4.895552811 -4.605475660 -4.436961783

SC(n) -3.449030454 -2.82350152 -2.350248120 -1.760723357 -1.292761870

FPE(n) 0.001412901 0.00172546 0.001859561 0.002330702 0.002704777

VAR Estimation Results:

=========================

Endogenous variables: e, prod, rw, U

Deterministic variables: both

Sample size: 82

Log Likelihood: -170.726

Roots of the characteristic polynomial:

0.9071 0.9071 0.9037 0.7092 0.7092 0.2549 0.166 0.166

Call:

vars::VAR(y = Canada, p = 2, type = "both")

Estimation results for equation e:

==================================

e = e.l1 + prod.l1 + rw.l1 + U.l1 + e.l2 + prod.l2 + rw.l2 + U.l2 + const + trend

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

e.l1 1.636e+00 1.510e-01 10.830 < 2e-16 ***

prod.l1 1.716e-01 6.280e-02 2.733 0.00789 **

rw.l1 -6.006e-02 5.628e-02 -1.067 0.28947

U.l1 2.740e-01 2.055e-01 1.333 0.18661

e.l2 -4.842e-01 1.648e-01 -2.938 0.00443 **

prod.l2 -9.766e-02 6.747e-02 -1.448 0.15207

rw.l2 1.689e-03 5.621e-02 0.030 0.97611

U.l2 1.433e-01 2.108e-01 0.680 0.49886

const -1.510e+02 6.921e+01 -2.181 0.03244 *

trend -5.706e-03 1.652e-02 -0.345 0.73077

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.365 on 72 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared: 0.9985, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9983

F-statistic: 5435 on 9 and 72 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Estimation results for equation prod:

=====================================

prod = e.l1 + prod.l1 + rw.l1 + U.l1 + e.l2 + prod.l2 + rw.l2 + U.l2 + const + trend

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

e.l1 -0.14817 0.26200 -0.566 0.5735

prod.l1 1.09881 0.10894 10.087 2.05e-15 ***

rw.l1 0.01519 0.09762 0.156 0.8768

U.l1 -0.57737 0.35641 -1.620 0.1096

e.l2 0.23300 0.28585 0.815 0.4177

prod.l2 -0.21942 0.11703 -1.875 0.0649 .

rw.l2 -0.09343 0.09750 -0.958 0.3411

U.l2 0.89061 0.36574 2.435 0.0174 *

const -2.16645 120.05179 -0.018 0.9857

trend 0.06729 0.02865 2.348 0.0216 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.6332 on 72 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared: 0.9802, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9777

F-statistic: 396.4 on 9 and 72 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Estimation results for equation rw:

===================================

rw = e.l1 + prod.l1 + rw.l1 + U.l1 + e.l2 + prod.l2 + rw.l2 + U.l2 + const + trend

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

e.l1 -0.24395 0.31673 -0.770 0.4437

prod.l1 -0.13328 0.13169 -1.012 0.3149

rw.l1 0.85895 0.11801 7.279 3.38e-10 ***

U.l1 -0.08787 0.43086 -0.204 0.8390

e.l2 0.21384 0.34556 0.619 0.5380

prod.l2 -0.05273 0.14147 -0.373 0.7105

rw.l2 0.07839 0.11787 0.665 0.5081

U.l2 -0.25445 0.44213 -0.576 0.5667

const 133.30872 145.12882 0.919 0.3614

trend 0.06806 0.03464 1.965 0.0533 .

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.7654 on 72 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared: 0.9989, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9988

F-statistic: 7398 on 9 and 72 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Estimation results for equation U:

==================================

U = e.l1 + prod.l1 + rw.l1 + U.l1 + e.l2 + prod.l2 + rw.l2 + U.l2 + const + trend

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

e.l1 -0.57610 0.11571 -4.979 4.23e-06 ***

prod.l1 -0.08790 0.04811 -1.827 0.071824 .

rw.l1 0.01182 0.04311 0.274 0.784807

U.l1 0.60019 0.15740 3.813 0.000287 ***

e.l2 0.38095 0.12624 3.018 0.003520 **

prod.l2 0.04321 0.05168 0.836 0.405937

rw.l2 0.04662 0.04306 1.083 0.282552

U.l2 -0.09492 0.16152 -0.588 0.558584

const 180.98536 53.01834 3.414 0.001056 **

trend 0.01276 0.01265 1.008 0.316798

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.2796 on 72 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared: 0.973, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9696

F-statistic: 288.2 on 9 and 72 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Covariance matrix of residuals:

e prod rw U

e 0.133242 -0.004968 -0.04005 -0.069553

prod -0.004968 0.400914 0.03445 0.008295

rw -0.040049 0.034449 0.58590 0.028808

U -0.069553 0.008295 0.02881 0.078193

Correlation matrix of residuals:

e prod rw U

e 1.0000 -0.02150 -0.14334 -0.68142

prod -0.0215 1.00000 0.07108 0.04685

rw -0.1433 0.07108 1.00000 0.13459

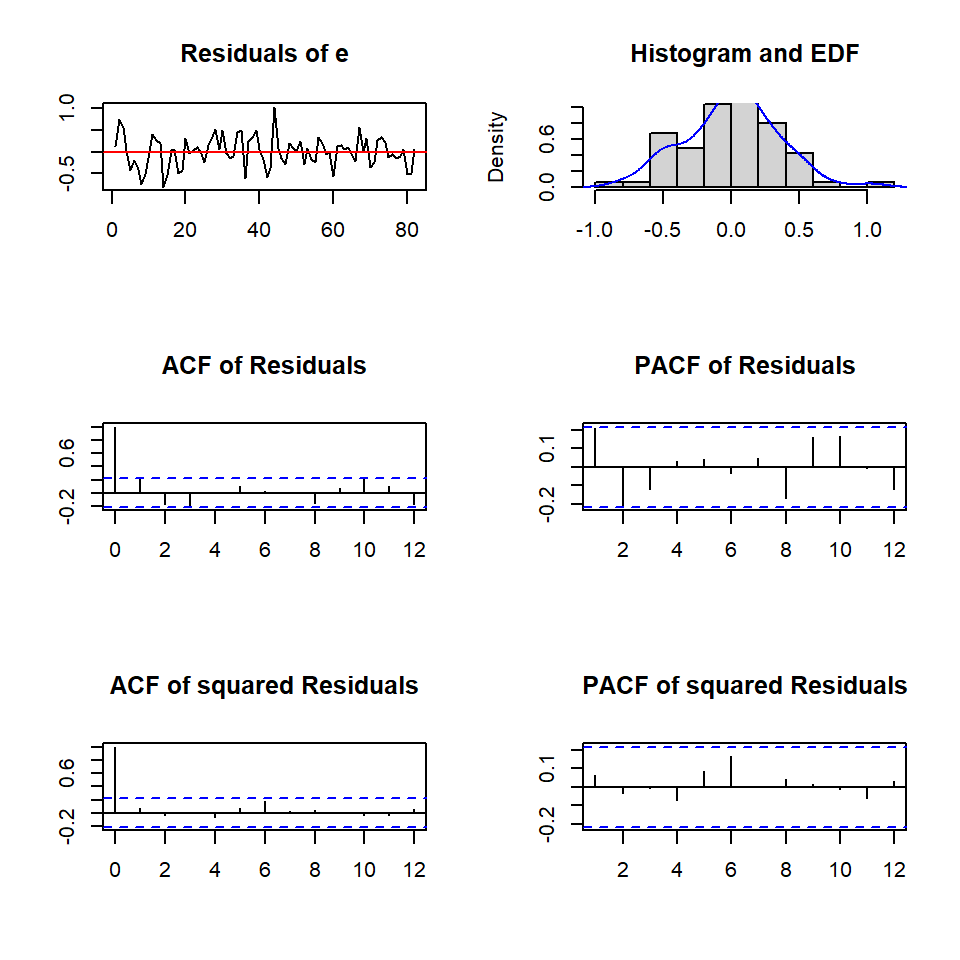

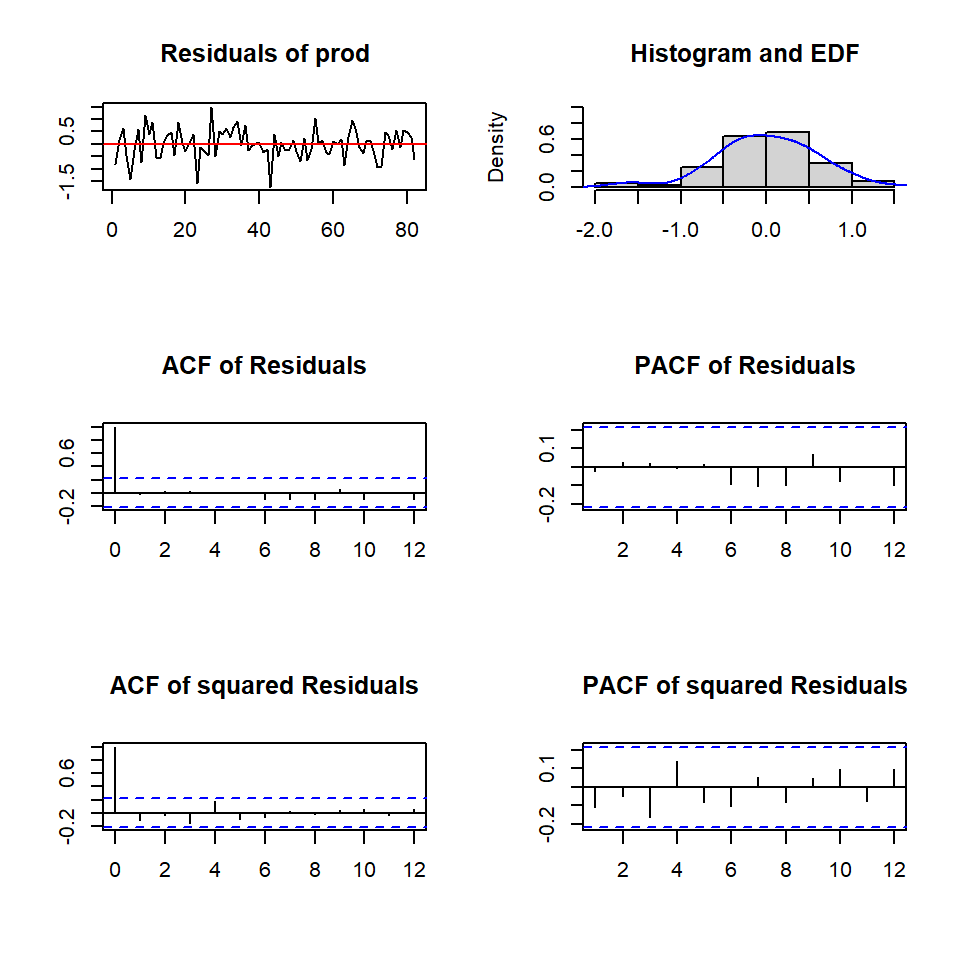

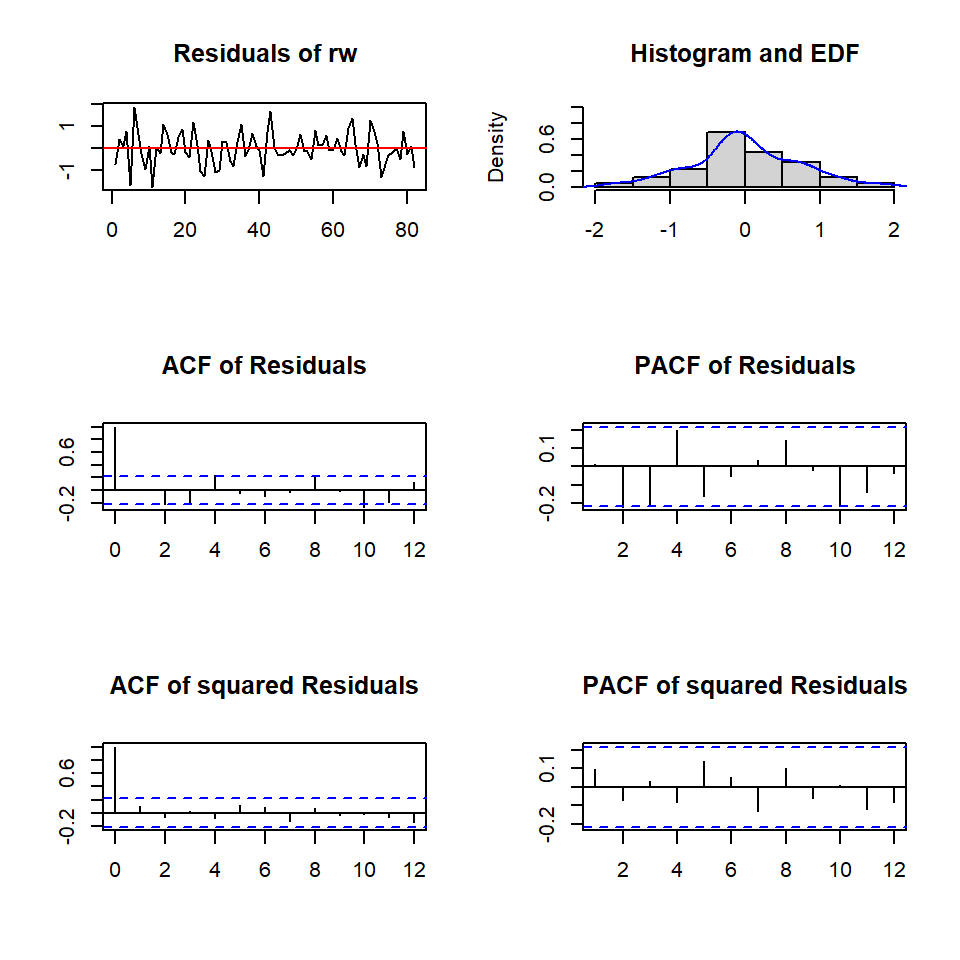

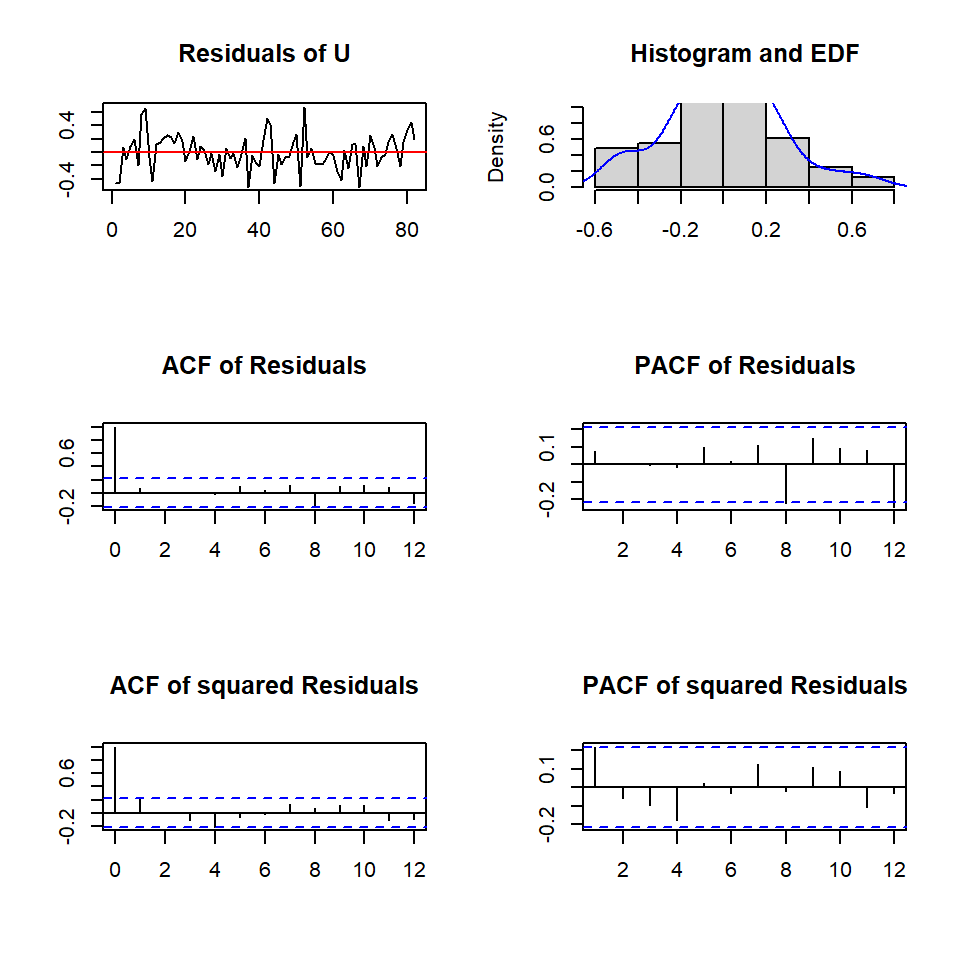

U -0.6814 0.04685 0.13459 1.00000Los diagnósticos

Portmanteau Test (asymptotic)

data: Residuals of VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 209.74, df = 224, p-value = 0.7443

ARCH (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 528.14, df = 500, p-value = 0.1855$JB

JB-Test (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 2.465, df = 8, p-value = 0.9633

$Skewness

Skewness only (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 1.3722, df = 4, p-value = 0.849

$Kurtosis

Kurtosis only (multivariate)

data: Residuals of VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 1.0928, df = 4, p-value = 0.8954Causalidad de Granger

$Granger

Granger causality H0: e prod rw do not Granger-cause U

data: VAR object fitvar

F-Test = 8.5625, df1 = 6, df2 = 288, p-value = 1.422e-08

$Instant

H0: No instantaneous causality between: e prod rw and U

data: VAR object fitvar

Chi-squared = 26.088, df = 3, p-value = 9.139e-06$Granger

Granger causality H0: prod rw do not Granger-cause e U

data: VAR object fitvar

F-Test = 2.964, df1 = 8, df2 = 288, p-value = 0.003337

$Instant

H0: No instantaneous causality between: prod rw and e U

data: VAR object fitvar

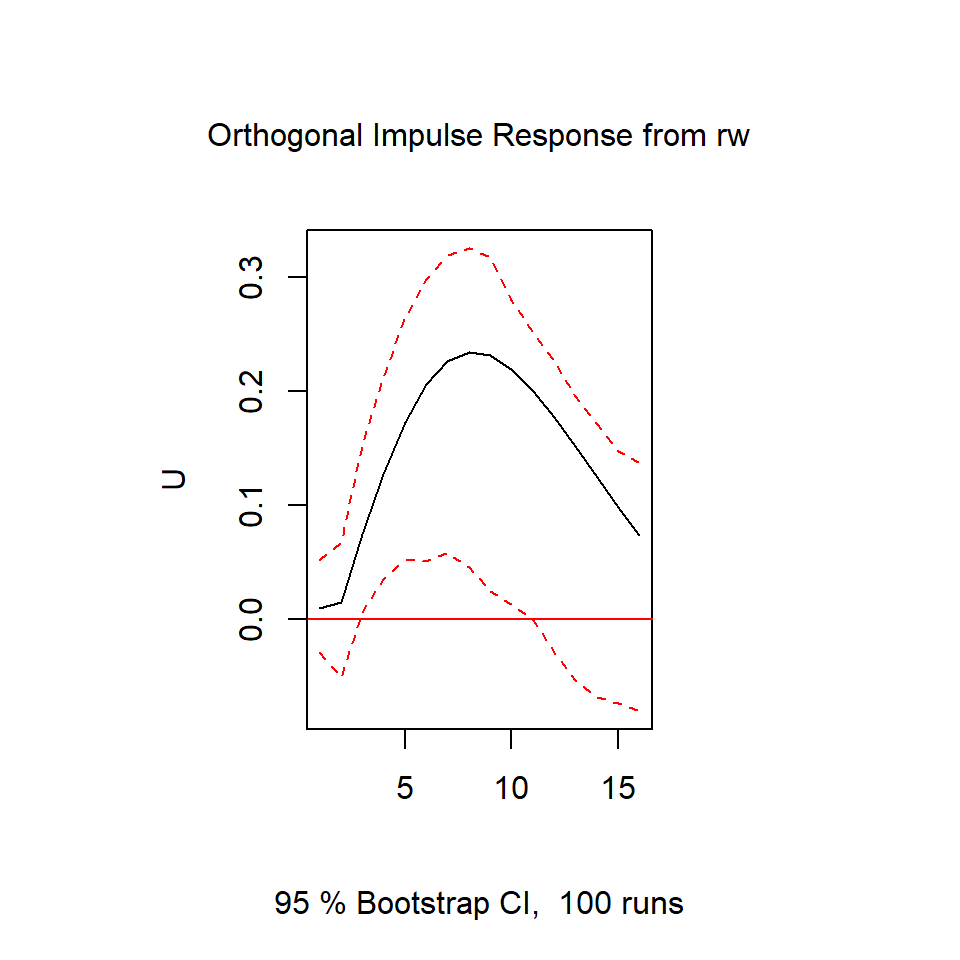

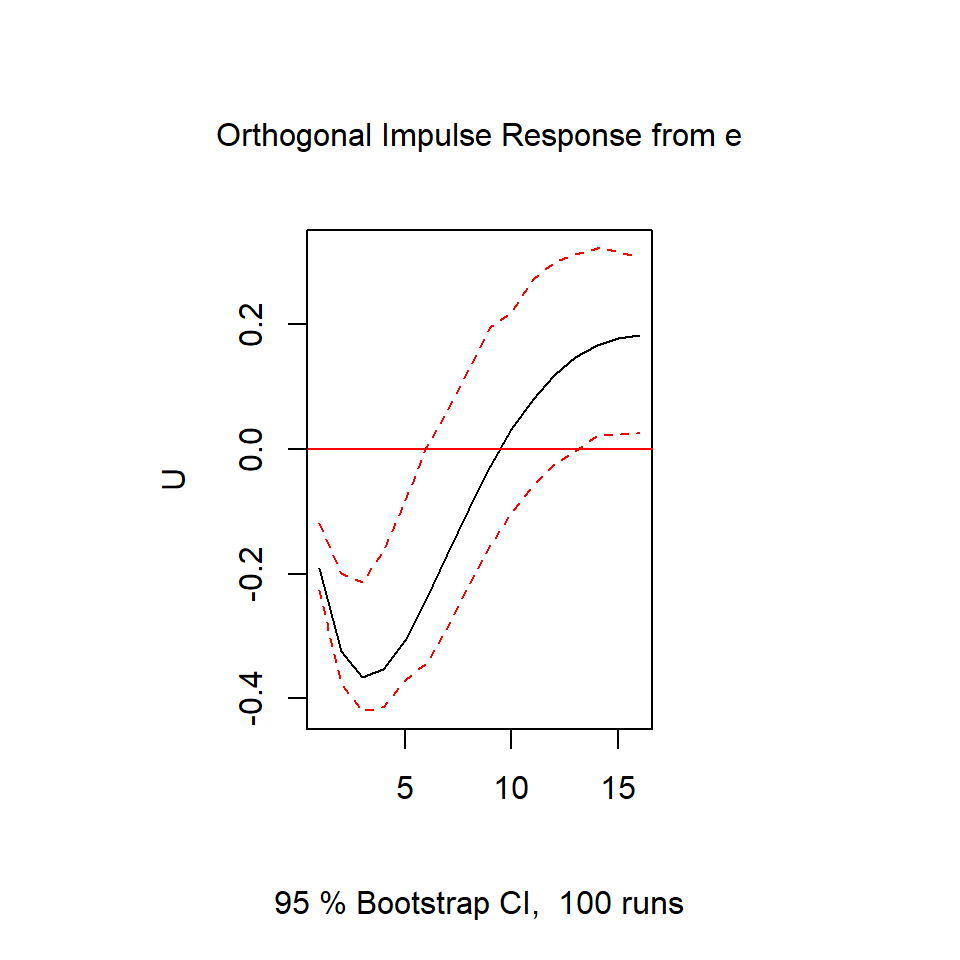

Chi-squared = 1.9934, df = 4, p-value = 0.737Análisis del impulso-respuesta

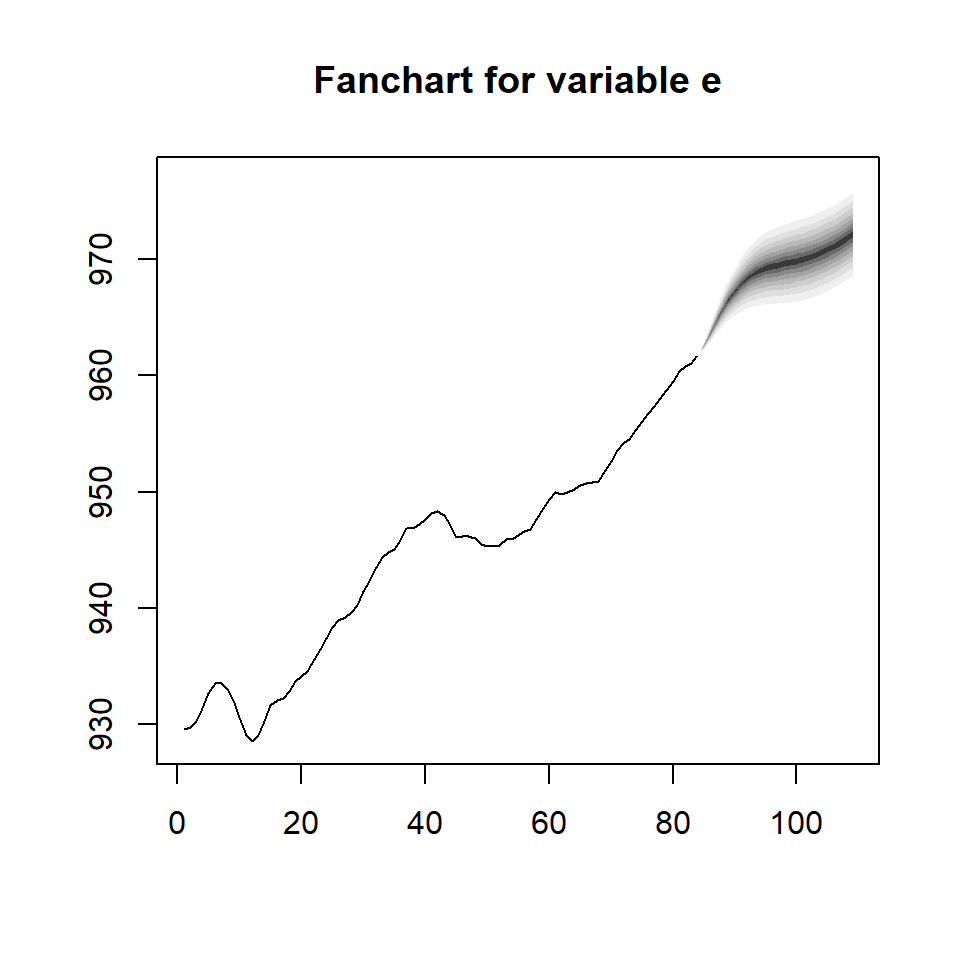

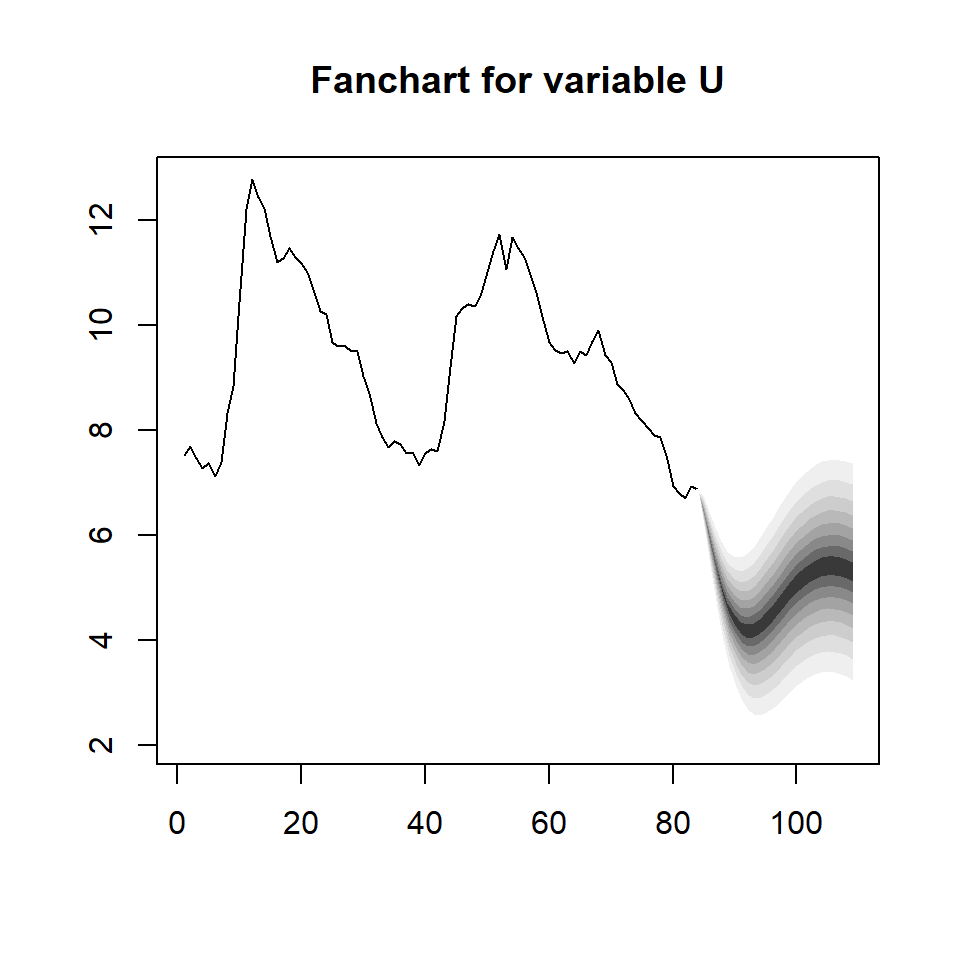

Predicciones

Paquetes en R

Para replicar los ejemplos de esta presentación, necesitan estos paquetes: